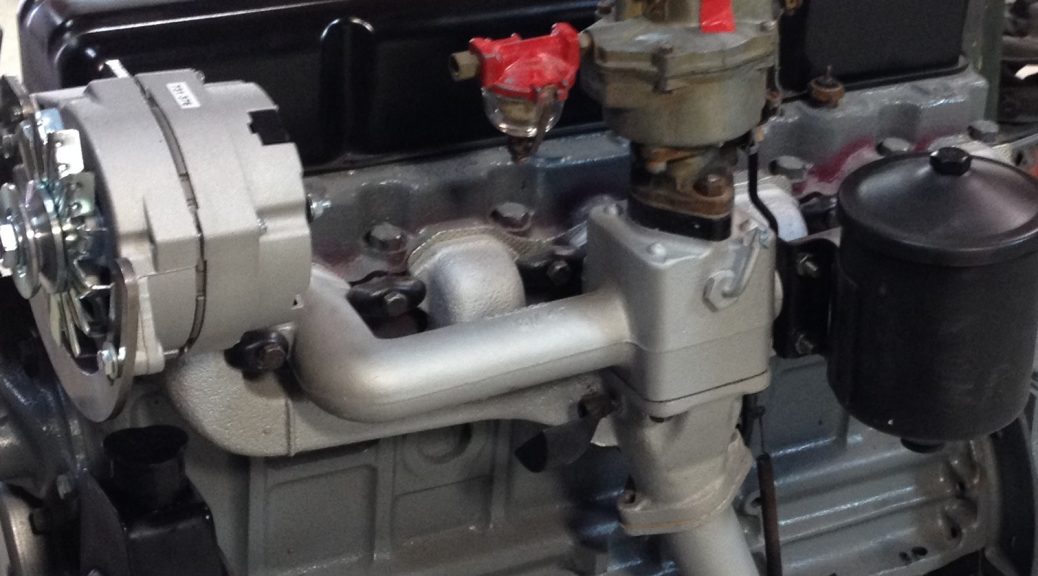

One of the peculiarities of the 235 c.i. six from our 1956 3/4 ton “Farm Truck” is that the bell housing is installed before the flywheel. Couple that with our desire to clean up, paint, and re-install the oil pan, and it became obvious that we should put the monster on an engine stand so we could rotate it.

All dressed up, the six weighs around 630 pounds, and it’s longer and taller than the Chevy small block V8. So we had concerns about putting it on a stand. We didn’t trust our own stand so a friend’s more stout-looking stand (1000 lb. rating) was borrowed.

Still, we had concerns about the length of the engine with bell housing installed, and could imagine it tipping over as we rotated it or moved it around the shop. To ease our minds, we added a 2 inch square tube “T” extension, with wheels, to the front of the stand for stability. We had the wheels in the shop, and the 5 foot long square tube set us back $6.50, so it was cheap insurance.

Since the bell housing sits considerably below the vertical center of gravity of the six, we attached the stand’s fixture such that round tube axis was much higher than bolts attaching it to the bell housing. It looked odd, but with grade 8 bolts holding it all together, there was no problem. We also backed up the upper bell housing bolts with nuts instead of relying on the bell housing’s internal threads.

We employed a four-foot long bar to rotate the engine once it was mounted to the stand, and we left the chain hoist attached for the first 90 degrees of rotation until we felt the balance was, indeed, going to be acceptable. With the long bar helping matters, it was easy for one person to rotate the engine with complete control. We pinned our “T” addition to the original stand with a spare bolt so that it would stay in place as we moved the engine around the shop.

All in all, it turned out to be no problem at all mounting the 235 six to our stand.